phylogeography

what is phylogeography?

[G]eology and biogeography are both parts of natural history and, if they represent the independent and dependent variables respectively in a cause and effect relationship, … they can be reciprocally illuminating.

–Rosen (1978, p. 776)

[C]omparative phylogeographic assessments within each of multiple codistributed species … offer perhaps the greatest hope for significant advances in understanding how … the demographic and natural histories of populations, can influence intraspecific phylogeographic patterns.

–Avise (1998, pp. 376-377)

In the past, molecular biology informed the methods of population genetics, while biogeographers operated independently of these fields. However, since the 20th Century molecular genetics revolution in systematics and population genetics, it is the tools of these fields that dictate methods for analyzing genetic data from natural populations, and this in turn has sparked a new field of ‘molecular biogeography.’ The growth of the ‘new’ biogeography is widely acknowledged to have particularly benefited from the rapid development of phylogeography. Yet, what is phylogeography?

Phylogeography is a relatively young and integrative field of science that uses molecular data to infer the processes influencing geographical distributions of genetic lineages within and among species, especially at the intraspecific level (Avise et al. 1987; Avise 2000). The phylogeography literature base has grown remarkably fast over the nearly three decades since the birth of the field, yielding many insights into the histories of biotas in different ecosystems across the globe, including cryptic and often temporally ‘deep’ genealogical divergences within many species ranges (e.g. reviewed by Beheregaray 2008; Knowles 2009). By linking these patterns of population divergence with data on geographical barriers, earth history events, distribution models, and speciation processes, phylogeography permits identifying and testing whether and over which temporal scales historical and recurrent processes have shaped intraspecific diversification in an area. Indeed, the reciprocal illumination that Rosen (1978; quoted above) envisioned for vicariance biogeography can also be achieved through phylogeography, as phylogeography provides means of inferring how species responded to geological processes without reliance on phylogenetic structure or areas of endemism required by other historical biogeography methods (Zink 2002); for example, historical processes from the unobservable past can still be inferred even when genetic breaks revealed by selectively neutral markers do not correspond to any present-day geographical barrier.

Moreover, because population or species demographic histories influence the shapes of their gene genealogies, we can use coalescent theory (a stochastic, backwards-in-time theory of genealogical processes; Kingman 1982) to estimate their underlying genealogies (e.g. by simulating a distribution of them) as well as population parameters describing their histories (e.g. past changes in population sizes) while accounting for various population genetic processes (e.g. subdivision, speciation, mutation, recombination; reviewed by Kuhner 2009). An important paradigm shift in phylogeography has been the realization that phylogeographic inferences are improved by developing and discriminating among competing coalescent-based demographic models using statistical methods that account for the stochasticity of genetic processes (Knowles & Maddison 2002; Knowles 2009; Nielsen & Beaumont 2009).

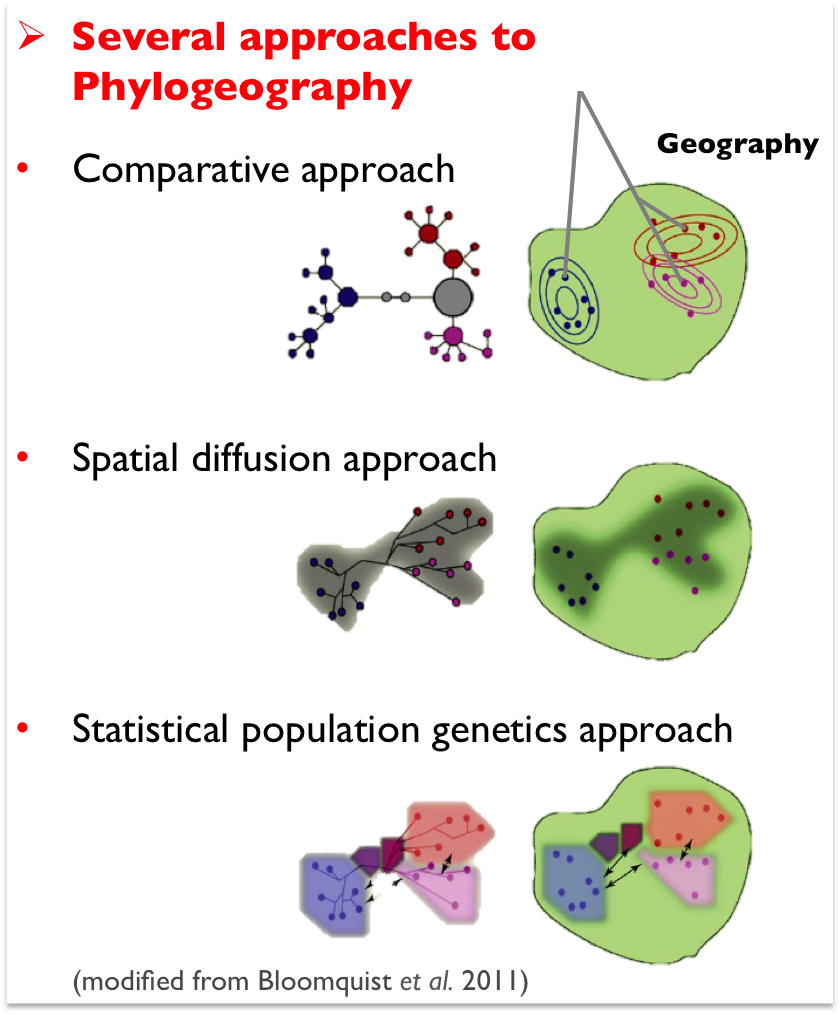

The above graphic (above-center) summarizes several 'paths' to phylogeographic inference reviewed by Bloomquist et al. (2010), including comparative, spatial diffusion, and statistical population genetics approaches, which each view the recovery of species demographic histories from different perspectives involving different forms of inferences (e.g. pattern-based methods; diffusion-model based inferences; and full-likelihood, full-Bayesian, and ABC model-based analyses).

my prior research in Phylogeography

Given I have discussed my ongoing research in phylogeography elsewhere in my About, Research, and Collaborators pages, this section provides a summary of my prior work in this fascinating and growing field, including studies conducted along two main lines of research:

- congeneric and comparative phylogeography

- model-based inference of species responses to Pleistocene climate and sea level change

congeneric and comparative phylogeography

While working towards my Master’s in Biology at UA, I asked what unique insights congeneric phylogeographical sampling (within a genus) might yield into understanding the phylogenetics and species limits of North American black basses (Centrarchidae: Micropterus), an iconic group of game fishes with a complex systematic and taxonomic history_. Based on sampling from across the geographical ranges of black bass species, we found multiple cases of mitochondrial introgression/hybridization events and a novel Gulf Coast clade representing a new lineage to science; thus phylogeography reveals a more complex view of black bass evolution highlighting population-level processes (Bagley et al. 2011, Biol. J. Linn. Soc.). I also combined mtDNA phylogeography, microsatellite DNA population genetics, and morphometric analysis to study Alabama Bass (M. henshalli_). I found that, despite evidence for hybridization with Redeye Bass (M. coosae), M. henshalli is overall genetically and morphologically distinct, particularly within the Tallapoosa River system (manuscript in prep.).

Comparative phylogeography provides a basis for more robust historical inferences (e.g. of historical biogeographical scenarios for a region) by searching for replicated geographical patterns across multiple codistributed species (e.g. Bermingham and Martin 1998), yielding insights into community assembly and diversification not possible through single-species phylogeography alone.

My Ph.D. dissertation work at BYU focused on using an integrative approach coupling comparative phylogeography with species delimitation to improve our understanding of the biogeography and species limits in complex tropical landscapes. The Central American (CA) land bridge and its freshwater stream fish assemblage provide an ideal study system for this research combining a complex/recent physical history with rich geomorphology and high endemism, including several codistributed lineages of freshwater fishes. My dissertation (1) developed and tested biogeographical hypotheses for CA through a synthesis of geological and phylogeographical data (Bagley & Johnson 2014a, Biol. Rev.); (2) analyzed single-species/lineage phylogeography datasets for up to eight lineages, including Poeciliidae (five lineages), Characidae (two species), and Cichlidae (one lineage, 4 spp.); and (3) ultimately scaled my own data and data curated from online repositories up to comparative analyses of 8 fish species/lineages (Bagley & Johnson 2014b, Ecol. Evol.; other manuscripts in prep.). Given a moderate to high degree of taxonomic uncertainty for various groups of Neotropical fishes I studied, this work also evolved to entail a component of species delimitation. Specifically, I used mollies in the Poecilia sphenops species complex_ _(Poeciliidae) as a model system for delimiting species and studying processes of diversification in widespread, morphologically conserved groups of Neotropical fishes, through coalescent-based analyses of multilocus genetic datasets. Therefore, the over-arching goals of my Ph.D. were to evaluate the impacts of historical processes (e.g. geological, climatic events) on geographical distributions of genetic lineages, to understand the relationship between species ecological differences and their phylogeographic histories, and to test and refine Central American freshwater fish species boundaries. I also worked with my Ph.D. advisor, Jerry Johnson, to build phenotypic datasets that will allow me to compare morphometric and life history variation with phylogeographic divergence using spatial-pattern analyses, to test hypotheses about selection and species limits.

While at BYU, I also developed research on the biogeography and evolution of Australian freshwater fishes in collaboration with Peter Unmack. By melding species tree analyses with phylogeographic inferences from mitochondrial and nuclear loci, we documented an Oligocene-Miocene origin for most species of galaxiid fishes in the genus Galaxiella (Galaxiidae), high genetic diversity, and strong evidence for a cryptic species within the threatened dwarf galaxias, G. pusilla (Unmack et al. 2012, PLoS ONE). Our findings weigh importantly on conserving this threatened clade of fishes, e.g. long-term planning should preserve multiple populations with unique alleles, in addition to the multiple ancient species in the group. I am currently working to expand my work in Australia to help develop a comparative perspective on the phylogeographic diversification of Australian freshwater fish assemblages. With Dr. Unmack, I am also presently working to expand phylogenetic systematics work on iconic game fishes, through a multilocus phylogenetic analysis of temperate perches in the family Percichthyidae, which are the largest fish species historically present in most temperate Australian freshwater habitats.

model-based inference of species responses to Pleistocene climate and sea level change

A product of the past two decades of analytical revolutions in biology has been the development of novel model-based statistical tools for (1) inferring parameters of ecological niches and predicting species past, present and future distributions, and (2) using coalescent simulations to arrive at objective rather than ad hoc inferences of processes influencing species phylogeographic histories. I am interested in using these toolsets, i.e. ecological niche modeling and statistical phylogeography, to test hypotheses and infer population history (e.g. lineage spread and range shifting), particularly the responses of species from unglaciated subtropical and tropical areas to climatic fluctuations of the late Pleistocene glaciations. For example, in our work on Galaxiella fishes, we documented a shared demographic-growth response across taxa associated with relaxation of aridity during the late Pleistocene, based on statistical comparisons of Bayesian demographic models using Bayes factors (Unmack et al. 2012, PLoS ONE). I then revisited the southeastern U.S. freshwater fish fauna to test the potential impact of expansion-contraction cycles on species ranges, hence patterns of genetic structure, during the last glacial cycle. Paleoclimatic modeling, phylogeography, and coalescent simulations using sequence data from least killifish, Heterandria formosa, suggested that this cold-intolerant species contracted its range to a peninsular Florida refugium during the Last Glacial Maximum (Bagley et al. 2013, BMC Evol. Biol.). We also found evidence for nuclear-mitochondrial discordances indicating evidence for historical gene flow and sex-biased migration.

future phylogeography research directions

While the review of my previous work on phylogeography above is informative, it is exciting to speculate about potential future research directions in this field. One thing I am very excited about regarding the future of my phylogeographical research is that I intend to continue the past lines of research above, while maintaining a ‘big picture’ view, by focusing on community and ecosystem-level syntheses. In addition, I look forward to developing the phylogeography arm of my research program along several lines of research, including:

- using model-based comparative phylogeography to infer community assembly and diversification,

- using landscape genetics and ecological niche modeling to explore the relative roles of ecology and geography in shaping genetic isolation in natural populations (with empirical analyses of Central American terrestrial and freshwater species), and

- using conservation phylogeography to aid resolving the 'Linnean' and 'Wallacean' shortfalls in biogeography and conservation, and to inform conservation management and policy, particularly in the Central American and South American Neotropics.

While I intend to conduct this research in my main geographical areas of focus, the South American (Brazil) and Central American Neotropics, I would be interested in pursuing conservation biogeography in my other study systems discussed on my Research page, or any other region of the world with a highly endemic and threatened biota. However, by extending phylogeography to inform management I will help us not only understand, but also conserve, the patterns and processes of diversification in unique Neotropical (and other) regions of the world.

References

Avise JC (1998) The history and purview of phylogeography: a personal reflection. Molecular Ecology, 7, 371-379.

Avise JC (2000) Phylogeography: the History and Formation of Species. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Avise JC, Arnold J, Ball RM, Bermingham E, Lamb T, Neigel JE, Reeb CA, Saunders NC (1987) Intraspecific phylogeography: the mitochondrial DNA bridge between population genetics and systematics. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 18, 489-522.

Bagley JC, Johnson JB (2014a) Phylogeography of the lower Central American Neotropics: diversification between two continents and between two seas. Biological Reviews, 89(4), 767-790.

Bagley JC, Johnson JB (2014b) Testing for shared biogeographic history in the lower Central American freshwater fish assemblage using comparative phylogeography: concerted, independent, or multiple evolutionary responses? Ecology and Evolution, 4(9), 1686-1705.

Bagley JC, Mayden RL, Roe KJ, Holznagel W, Harris PM (2011). Congeneric phylogeographical sampling reveals polyphyly and novel biodiversity within black basses (Centrarchidae: Micropterus). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 104(2), 346-363.

Bagley JC, Sandel M, Travis J, Lozano-Vilano M de L, Johnson JB (2013) Paleoclimatic modeling and phylogeography of least killifish, Heterandria formosa: insights into Pleistocene expansion-contraction dynamics and evolutionary history of North American Coastal Plain freshwater biota. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 13, 223.

Unmack PJ, Bagley JC, Adams MD, Hammer MD, Johnson JB (2012) Molecular phylogeny and phylogeography of the Australian freshwater fish genus Galaxiella (Teleostei: Galaxiidae), with an emphasis on dwarf galaxias (G. pusilla). PLoS One, 7(6), e38433.

Beheregaray LB (2008) Twenty years of phylogeography: the state of the field and the challenges for the Southern Hemisphere. Molecular Ecology, 17, 3754-3774.

Bermingham E, Martin AP (1998) Comparative mtDNA phylogeography of neotropical freshwater fishes: testing shared history to infer the evolutionary landscape of lower Central America. Molecular Ecology, 7, 499-517.

Bloomquist EW, Lemey P, Suchard MA (2010) Three roads diverged? Routes to phylogeographic inference. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 25, 626-632.

Knowles LL (2009) Statistical phylogeography. Annual Review in Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 40, 593-612.

Rosen DE (1978) Vicariant patterns and historical explanation in biogeography. Systematic Zoology, 27, 159-188.

Zink RM (2002) Methods in comparative phylogeography, and their application to studying evolution in the North American aridlands. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 42, 953-959.